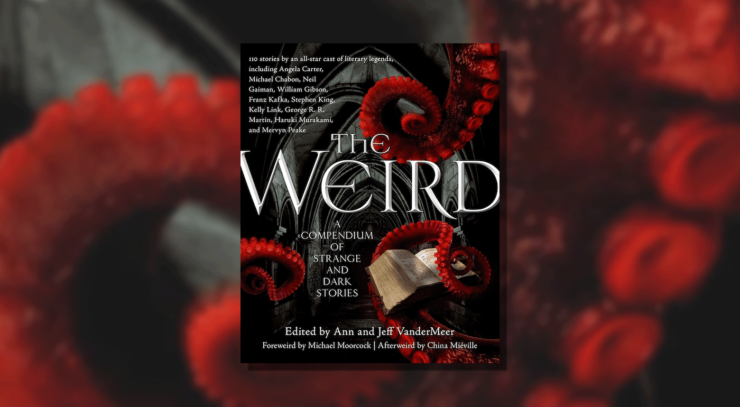

Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches. This week, we cover H.F. Arnold’s “The Night Wire,” first published in the September 1926 issue of Weird Tales and collected in Ann & Jeff VanderMeer’s anthology, The Weird. Spoilers ahead!

Jim is the night manager of a wire office in a western seaport city. “There’s something uncanny about these night wire jobs,” he writes. You listen “to the whispers of a civilization. New York, London, Calcutta, Bombay, Singapore—they’re your next-door neighbors after the street lights go dim and the world has gone to sleep.” The night wire man takes down the news of every disaster “almost in his sleep, picking it off on his typewriter with one finger.”

Queer things do happen sometimes. Jim wishes he could get over one particular instance, but he hasn’t yet.

There is—no, was—only one night operator on Jim’s staff. John Morgan was a man in his forties, sober and hardworking. Morgan was one of only three “double men” Jim’s ever met. He could take down stories from two wires at the same time, typing them up on two different typewriters, hour after hour, making no mistakes. “He was a wizard, a mechanical automatic wizard which functioned marvelously but was without imagination.”

On the night in question, Morgan mentions that he’s tired and finds the room “close,” but he settles into his work as usual. Only one wire is transmitting as three a.m. rolls around. Every ten minutes or so, Jim collects Morgan’s copy for sorting and review. It’s the usual stuff until, oddly, Morgan opens the second wire. His copy from the first wire remains the usual stuff. But the copy from the second wire catches Jim’s attention because it’s from a town he’s never heard of: Xebico.

Jim has saved a duplicate of the Xebico dispatches, and can put them down verbatim. Wherever this city is, it’s experiencing unprecedented weather. A heavy fog that has descended on the city, defying lights to pierce it, stopping traffic, steadily growing denser. By evening, Xebico is pitch dark. Still stranger, the fog is accompanied by an unfamiliar “sickly odor.” Morgan, Jim notices, has slumped in his chair and directed his work lamp so it illuminates only the tops of his typewriters. His fingers, however, are as deft as ever.

From Xebico: A village sexton arrives at the local wire office in hysterics, claiming that the fog originated in his churchyard. It billows into queer forms that writhe in anguish. Something else moves in the fog, but the sexton fled without seeing it clearly, driven by screams from the neighboring houses. He’s admitted to a hospital, unconscious. Two search parties go to the church. Neither return. The fog invades homes through every crack, bringing with it an oppressive odor of dead things. Terrified townspeople gather in the main church as, from the outskirts, cries come like wind whistling through a tunnel. Yet there is no wind.

Jim has never been so unnerved in a dozen years of listening to the wire news. He looks out a window and wonders if he sees a faint trace of fog in the city canyons far below—no, just his imagination. Morgan, head sunk between his shoulders, looks asleep but continues to type. Jim stands behind his chair and reads the Xebico dispatches word by word. The wire operator in that cursed city writes that his office has stopped receiving bulletins from outside. He will stay with the wire, however, until the end. From his window, he can look down into a thick blanket of blackness and hear wails. He fears these are death cries, and they’re coming closer to the city center. The fog swirls in contortions “of almost human agony.” Occasionally it parts to give him a glimpse of the streets where people run screaming amid the “immense whistling of unseen and unfelt winds.”

Then, directly below the Xebico operator, a break reveals that the fog is not mere vapor but alive. Beside each human is a “companion figure, an aura of strange and vari-colored hues” that clings and caresses. They are—but the operator dares not say. But the writhing human bodies are being stripped. Are being consumed “piecemeal.”

Hot vapors obscure the horrific sight, but there’s a new wonder. The fog begins to change colors, not of its own accord but reflecting an overarching sky that has burst into flames. The fires burn the operator’s eyes and twist into “a kaleidoscope of unearthly brilliance.” He feels that these lights radiate “force and friendliness, almost cheeriness. But by their very strength, they hurt.” The lights descend a million miles at a leap. The fog melts beneath them. Again he sees the streets, which are full of people. Then the lights are all around him, enveloping, and—

The wire to Xebico goes dead. Jim looks at Morgan, whose hands have dropped to his side and whose body hunches peculiarly. Jim directs the work lamp toward Morgan’s face and sees that his eyes are fixed, staring. Jim calls the Chicago office that has been transmitting to the second wire, but they say Wire Two hasn’t been used all night.

Jim shouts to Morgan that the Xebico horror isn’t true, they’ve been hoaxed. But Morgan is cold, dead for hours. Could “his sensitized brain and automatic fingers [have] continued to record impressions even after the end?”

Jim has searched world atlases for Xebico, and found no town of that name. Whatever killed John Morgan will remain a mystery, but he knows he’ll never work the night shift again.

What’s Cyclopean: The fog originates as a “subterranean breeze” from the graveyard. The voices within echo in “queer uncadenced minor keys.”

Libronomicon: We never do learn whether these wire reports end up in the paper the next day. I’m guessing not.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The Xebico church sexton arrives in hysteria, reporting unbelievable stories of the fog’s origins. Eventually he works himself into a swoon—or maybe a coma, as one doubts he survives long enough to distinguish the two.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

VanderMeer’s introduction to “The Night Wire” is oddly apologetic about the “dated aspects” of the story. I assume this refers to the central role of a news wire. But while I’ve heard of kids unable to relate to characters who lack smartphones, that’s far from universal. (My own can handle The Wizard of Oz and Goosebumps books with equal aplomb.) And the readers of a 102-year retrospective anthology presumably have some mental flexibility about these things.

I, personally, find older news technologies comforting—the idea of some linear set of developments, watched over by responsible typists and reported in due course, is a warming bit of nostalgia in these days when media itself is eldritch. (I dare you not to be stirred by this scene from The Post—and if I were going to apologize for anything, it would not be the tech but the dude-ful-ness of it all.) Which makes the intrusion of the eldritch into that controlled process all the more disturbing.

In 1926, it would’ve been an all-too-familiar intrusion. The technology may have been more linear, the routes of communication more tailored to the bounds of human attention, but the events were no more comforting than those that come at us from a thousand directions now. The news from Xebico was everywhere.

The fog that first hides, and then reveals, the fate of the town, might be the fog of chemical weapons in the trenches of Europe. Or it might be London’s pervasive smog, with its regular and often deadly surges. It might also be the precursor to weird fiction’s own periodic mists; it’s certainly the earliest I’ve seen. Though I imagine that fog has always frightened, and this one doubtless has its own ancestors. It’s an excellent and disturbing example of its kind, odiferous as well as visual, and full of… something. Monsters? Demons? Avenging angels? Ghouls?

The latter seems all too plausible, and the influence on Lovecraft clear—not only in the upwelling anthropovores, or in the danger heralded by “colors as yet unseen by man or demon,” but in the ending. The lights that approach through the fog are painful in their strength, and yet “radiate force and friendliness,” containing “nothing harmful” even as they harm. Is this not wonder and glory? Indeed, I think Arnold does a better job than Lovecraft of persuading that this last-minute change of heart is an ultimate horror, rather than a revelation of truth. But then I would think that, wouldn’t I?

(Anne below reads the “harmless” lights and the fog as in conflict, whereas I read them as different aspects of the same apocalypse. The resolution of this ambiguity will have to be left for some future interdimensional explorer.)

I am also a complete sucker for stories of people sticking to their posts, even as deadly force overwhelms them, to make sure the word gets out. Vince Coleman, urging an incoming train to avoid the Halifax Explosion. Reporters staying in war zones, because getting the story out is more important than personal survival. The unknown operator in Xebico fits this profile, making for a more plausible source of last-minute apocalyptic detail than any terrified scrawler of “The window! The window!” or “Aaaaaaahhhhh!” Perhaps the stolid Morgan is a similar hero, literally dying to share the news from somewhere otherwise lost to the world.

Anyway, if you like this story, you can now follow the local Xebico news on X, YouTube, Bluesky, Facebook, Google News, TikTok, Reddit, and many other sites. If you don’t want to follow the local Xebico news… sorry. I’m afraid you’ve got no choice.

Anne’s Commentary

According to The Weird’s introduction to “Night Wire,” Lovecraft “is said to have loved this story.” So did many other Weird Tales readers. In these days of online magazines, readers can instantly express their opinions. Not so in the days of the pulps, when editors had to rely on posted letters to figure out which offerings were winners and which were duds. I dug into the musty PDF files of WT and found that Farnsworth Wright had a closing column called “The Eyrie,” in which he published reader comments, albeit a couple of months after the issue in question. He encouraged comments by including a “coupon” that readers could cut out and mail to “The Eyrie.” It gave space for one’s favorite stories in that issue, plus remarks. Ditto space for the stories one didn’t like, and why.

“Night Wire” appeared in the September 1926 issue. In the November 1926 issue, Wright singled out praise from Albert Elmo Morgareidge of St. Louis, who “as a printer by trade, and a newspaper man,” voted for Arnold’s story as the best of September 1926. Wright adds his own opinion:

“The showing made by The Night Wire, by H. F. Arnold, in the voting was one of the agreeable surprizes in the balloting for favorite story in the September issue. This story was only a four-page ‘filler’ story, buried in the magazine without even an illustration, yet it drew so many votes that it ranks right behind the three leaders in popularity with the readers. The Night Wire is the type of utterly ‘different’ story that we are always looking for, the type that causes the editor to chortle with glee when he gets one in the day’s mail. And such utterly bizarre and ‘different’ stories are as nectar and ambrosia to the reader who is sated with the humdrum magazine fare of today.”

In several sites I searched, Arnold is identified as Henry Ferris Arnold, Jr. (b. 1902 – d. 1963.) In his excellent blog Tellers of Weird Tales, Terence E. Hanley profiled the author as Henry Ferris Arnold, Jr., but later struck out the material related to that person, adding he’s not sure he has the right H. F. Arnold. Stephen Graham Jones has written a story based on “Night Wire” called “Xebico”, which delves into the mystery of the author’s identity.

Whoever H. F. Arnold was, I hope that they basked in Wright’s comment. Weird lit praise don’t get much finer.

To return to Lovecraft, and why he would have loved “Night Wire.” Farnsworth Wright’s verdict that it’s utterly bizarre and different may be explanation enough. More specifically, its bizarreness hinges on the way news from “nonexistent” Xebico arrives in a wire office on Earth. The normal way such news arrived in the 1920s was via telegraph wire, with the content in Morse code. Jim doesn’t exaggerate when he calls John Morgan a “wizard”—the man’s capable of real-time translation from Morse code to English text of not one but two wire transmissions—simultaneously!

Jim adds that Morgan’s superpower is of a “mechanical automatic” nature, and that the man himself is “without imagination.” There may be envy there, but if Morgan has never said a word about himself in three years, I can understand Jim’s assessment. Extreme focus and facility in one task combined with a certain disconnection, a certain limited outlook, might make Morgan a perfect receptacle for an invading alien mind. I think of the “degenerate” Joe Slater in Lovecraft’s “Beyond the Wall of Sleep,” whose “harmless stupidity” and “bovine, half-amiable normality” made him easy prey for a possessing “cosmic entity.” The title character of Lovecraft’s “Music of Erich Zann” is another victim (?) of an outside intellect that uses him as an expressive conduit.

Tellingly, Morgan’s only personal communication to Jim is that he’s “feeling tired” that night. Shortly afterwards, he asks Jim if it doesn’t feel “close” in the office. His fatigue and breathlessness could be symptoms of a pending heart attack or stroke. When the cardiac or cerebral accident hits Morgan, he may die at once, leaving his “mortal coil” open for an operator from beyond—perhaps the Xebico operator, who’s lost connection with his usual channels but must report his world’s apocalypse to someone.

And Xebico is in the grip of catastrophic conflict between the death-stinking fog and some celestial “quintessence of all light” that sears yet feels friendly. When the light melts the fog, the Xebiconians to whom strange-hued devourers clung moments before look restored to the Xebico operator, who is himself enveloped in light. End of transmission.

So, a happy ending for Xebico, with the forces of light defeating the forces of obscuration? I don’t know. “Night Wire” feels too short to chronicle the ultimate confrontation of Good versus Evil. The increasingly eerie atmosphere and rising tension in Jim’s two-man office, high above the sleeping western seaport, is the story’s strength, undeniable.

There’s no happy ending in Jim’s office, with Morgan dead and Jim psychically scarred into taking the day shift, which just doesn’t have the journalistic romance of the night wire so compellingly conveyed in the story’s opening. All those exotic locations hovering close in the darkness. Calcutta, Bombay, Singapore. Xebico.

Maybe day shift’s not so bad. The doughnuts are freshest then.

Next week, is Louis going to wake up? Is Rachel going to get home? Is Jud going to miss the whole thing? Find out with us in Chapters 58-60 of Pet Sematary.

First thing’s first, GNU John Morgan. You did your service to the wire diligently!

I understand why readers loved this one. It starts out creating such a beautiful, noir atmosphere in that little wire office, and then slowly feeding in the horror. And imagine how slow it must have been for Jim, as Morgan is tapping it out one letter at a time. I agree with Ruthanna that I love the bit of older technology here – just imagining how every step of that process had a human touch, In addition, for some reason I was reminded of a Reread in the same anthology from many moons ago, Robert Barbour Johnson’s “Far Below”. In both we are seeing some horror far older than us sneaking through newly-created channels. In this case, the wire, in the previous, the subway.

However, this problem can’t be solved with machine guns. In fact, I agree with Ruthanna – this problem can’t be solved at all. When that bright light came down from the sky, at first I thought, “oh man, what kind of August Dereleth Manichean bs is this..” But then, Xebico disappeared. Was this news from another world? Or were John and Jim the last people to remember a town that has been erased from existence by a force beyond reckoning? And questions like that are why it’s good.

Also, thank you Anna for linking that Stephen Graham Jones story!

We’re probably going to do that SGJ story in a couple of weeks, because how can we resist?

Good thing I didn’t just buy the reprint of After the People Lights Have Gone Off or anything…

It’s so good!